A painter, architect and father of modern gardening. In the first… he was below mediocrity; in the second he was a restorer of the science, in the last an original…

Horace Walpole, who thought Kent’s real talent was for landscape design

Credited as having introduced the Palladian style of architecture into England and originating the ‘natural’ style of gardening known as the English landscape garden, Kent was a polymath, who also turned his hand to designing sculpture, furniture, metalwork, book illustration, theatrical design and costume.

Through his architectural commissions Kent moved onto developing the surrounding landscape. He had a vision that all landscape should be viewed as a classical painting remarking that ‘all gardening is landscape painting’, with sympathetic arrangements to maximise the artistic effects of shape, light and colour.

Sample the arcadian landscape at Stowe and find out more about the man who influenced this little slice of 18th century paradise – William Kent. Now in the care of the National Trust, Stowe is one of the finest examples of landscape gardening.. For more information about Stowe go to: https://nationaltrust.org.uk/stowe

Georgian designer

Image: In this self-portrait from the ceiling of the King’s Staircase at Kensington Palace, Kent is dressed in brown, with his mistress Elizabeth Butler next to him.

Yorkshire-born William Kent began his working life as a sign and coach painter. His employer recognised his greater talent, and Kent was sent to study art in Italy, thanks to several wealthy patrons. William, a charming and skilful social climber, made several influential friends on his travels, including the wealthy and sophisticated Earl of Burlington.

Skilful social climber

In 1719, William Kent returned to London from his Italian travels, looking for work. His friend Lord Burlington used his high ranking contacts to introduce the young artist to the royal household.

George I was searching for a ‘dazzling’ painter to decorate his new state apartments at Kensington; Kent saw his chance. He undercut the official royal painter, Sir James Thornhill’s quote by several hundred pounds, and won the job.

Did you know?

Kent’s first royal commission stirred up jealousy: a highly-critical rival suggested that he had cheated on his materials to save money!

The room that launched a career

With his rivals brushed aside, and with George I’s blessing, Kent set to work on the largest of the state apartments, the Cupola Room.

He was closely monitored by a nit-picking committee from the Office of Works, but his new fashionable Italianate style (and Kent’s powerful friends) tipped the balance of opinion in his favour. And George I loved the clever décor, full of eye-tricking illusions.

Kent made the whole room resemble a four-sided Roman cupola (a rounded dome). The illusion is enhanced by the steeply curved ceiling, with the Garter Star at its apex.

Image: At the centre of the Cupola Room is an 18th-century musical clock, known as the ‘Temple of the Four Great Monarchies of the World’.

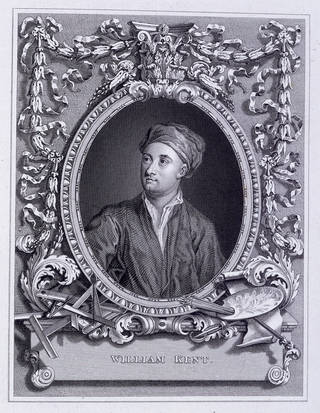

BIO | William Kent biography

“All gardening is a landscape painting”

William Kent

Rousham Court, Oxfordshire

William Kent was born in Bridlington, Yorkshire, in 1685. He trained as a sign painter, and also worked on coaches, before taking up landscape painting. Unfortunately, his talent with the brush was not up to his vision. For 10 years Kent lived and studied painting in Rome while he made a living by buying paintings and selling them to the English aristocracy as house furnishings.

In 1715 Kent met Lord Burlington, and Burlington was so impressed with Kent’s artistic vision that he brought the young Yorkshireman back to London with him. There Kent designed and built furniture and temples on a classical theme for Burlington and his friends.

He also continued with his painting, but at Burlington’s urging, he branched into architecture, where he became quite fashionable.

Kent’s finest architectural work is undoubtedly Holkham Hall, built for the Earl of Leicester in the Palladian style. Architecture then included more than simple house design, and Kent was involved in the creation of interior fittings and furnishings, most designed in an ebullient Baroque fashion.

It is not as an architect that Kent is famous, however, but as the father of the “picturesque”, or English landscape garden. Yet Kent was no horticulturalist – he envisioned the landscape as a classical painting, carefully arranged to maximize the artistic effects of light, shape, and colour. He was not above planting dead stumps to create the mood he required.

His gardens were dotted with classical temples replete with philosophical associations, a fact which would have been readily apparent to his learned patrons.

Kent’s most important gardening creations were at Stowe, Rousham, and Chiswick House. At Stowe, he smoothed away the rigid lines of the formal gardens to create sinuous shaded walks.

William Kent died in 1748, but his contributions to the ‘natural” gardening style which evolved into the English landscape garden cannot be overstated.

William Kent (1685 – 1748) was the leading architect and designer of early Georgian Britain. Credited as having introduced the Palladian style of architecture into England and originating the ‘natural’ style of gardening known as the English landscape garden, Kent was a polymath, who also turned his hand to designing sculpture, furniture, metalwork, book illustration, theatrical design and costume.

Kent’s life coincided with a major turning point in British history – the accession of the new Hanoverian Royal Family in 1714. He played a leading role in establishing a new design aesthetic for this crucial period when Britain defined itself as a new nation.

Kentino: the ‘Signor’ in Italy

Kent was originally from Bridlington in Yorkshire, but like many of his contemporaries was drawn by the allure of Italy. From 1709 to 1719 he studied in Rome, copying Old Master paintings and learning the techniques of etching and engraving. He travelled throughout Italy where he met important figures such as Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington. Lord Burlington would become his best-known patron and secure him a series of career defining commissions back in Britain. Part of Kent’s appeal for these English clients was a powerful nostalgia for their Italian tours. A jovial house guest of his patrons, ‘Kentino’ or ‘the Signor’ (as he was affectionately known) had the habit of suddenly breaking into Italian in his letters. The heavy, gilded style of furniture and interiors that took his name – ‘Kentian’ – was largely inspired by the richly decorated interiors of the Italian Baroque palaces that Kent’s patrons had been taught to understand and appreciate during their Grand Tours.

William Kent: Designing Georgian Britain, on view at the Bard Graduate Center: Decorative Arts, Design History, Material Culture from September 20, 2013 to February 9, 2014, is the first major exhibition to examine the life and career of one of the most influential designers in eighteenth-century Britain. Organized by the Bard Graduate Center in collaboration with the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, the exhibition is curated by Susan Weber (BGC) and Julius Bryant (V&A). Two of Kent’s most important gardens, at Rousham and Stowe, remain today close to Kent’s original designs. This video offers a virtual journey through these gardens.

A mission of taste

Kent arrived back in England during a transformational time in British culture. The last Stuart monarch, Queen Anne, had died in 1714, and the Hanoverians, led by George I, became the new ruling dynasty. The artistic styles of France and the Low Countries were associated with the Stuart regime and fell out of fashion. A search began for a new style that would define the United Kingdom.

Wealthy aristocrats looked to the art, architecture and design of Italy for inspiration, believing that society could be renewed and improved by a new direction in art and culture. They spread their ideas through books and new journals that encouraged the discussion of Art by an expanding middle class. It was in this context that Kent re-launched his career in Britain. Together with Lord Burlington he championed a form of design inspired by the classical architect Vitruvius, the British architect Inigo Jones (1573 – 1652) and the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508 – 80). Burlington began to design buildings for himself and his friends that were based on ancient models. He also sponsored several publications to promote the new Anglo-Palladian style.

From painter to architect of interiors

By 1725 William Kent had begun to extend his art from ceiling and wall paintings to the design of their settings. Kent was the first British designer to tackle an interior as a whole. Picture frames, door surrounds, fireplaces and furnishings started appearing in his design drawings. Kent designed interiors for several well-known houses, including Houghton Hall in Norfolk, Wanstead House in Essex, and Burlington’s own villa at Chiswick. He also designed interiors and furnishings for ‘power houses’ – the London residences of leading political and court figures. In the intensely competitive pinnacle of society, these houses were stages on which hosts and guests performed to set new standards in hospitality and taste.

Kent’s career coincided with a phenomenal increase in country house building and development. The Georgian governing class spent half the year in London, but also maintained a country seat where they entertained their peers. Owners also allowed respectable visitors to view their houses and collections. In this way Kent’s interiors would have been experienced by many.

Capital commissions

Lord Burlington realised that the surest way to entrench his stylistic revolution was to use the Office of Works – the department of the Royal Household responsible for all public buildings and their interiors. Under George I and his son George II, the new Hanoverian dynasty also recognised the propaganda value of associating themselves with the reformed national style, using it to reinforce the legitimacy of their monarchy. Through their patronage and a series of official posts in the Office of Works, Kent came to dominate the artistic presentation of the new regime. Kent’s two major public buildings, the Treasury and the Horse Guards, still stand in the heart of Whitehall.

William Kent’s designs for Parliament

In the 1730s William Kent worked on a series of designs for an entirely new, self-contained Parliament House. Initially working in collaboration with his friend and patron Lord Burlington, Kent quickly developed his own ideas about how the power of parliamentary ministers could be represented through architecture. He envisaged the new Parliament building as a fully mature statement of the Anglo-Palladian style and his designs were heavily influenced by Italian examples. Although ultimately unrealised, this was a major project for which Kent proposed several different schemes over a period of eight years (1733 – 39).

In this film Dr Frank Salmon, Senior Lecturer in History of Art at the University of Cambridge, reconstructs, for the first time, the complex sequence of Kent’s schemes for Parliament House.

We use third-party platforms (including Soundcloud, Spotify and YouTube) to share some content on this website. These set third-party cookies, for which we need your consent. If you are happy with this, please change your cookie consent for Targeting cookies.Show Purposes

The new monarchy

Kent’s first Royal Commission was to paint the new state rooms at Kensington Palace. This project launched his career in Britain and for the rest of his life he enjoyed the patronage of the Royal family. In addition to commissions from King George II and his wife Queen Caroline, Kent also worked for their eldest son, Frederick, Prince of Wales. Kent was a particular favourite of his and in 1732 Frederick granted him the official title of Architect to the Prince of Wales.

Holkham Hall

Holkham Hall in Norfolk is the most perfect surviving country house of the Anglo-Palladian movement and the most complete example of Kent’s work. It was the home of Thomas Coke, a wealthy commoner who rose to become Earl of Leicester. Kent and Coke had travelled together in Italy and Coke remodelled his inherited Norfolk estate, building a new house as a showcase for his remarkable and extensive Grand Tour collection of books, sculpture and painting.

Coke collaborated fully on the design and building of Holkham, assisted by the architect Matthew Brettingham. The plans were submitted to Lord Burlington for his approval. Holkham is therefore the work of four men and their respective contributions are the subject of debate. The house took a generation to build. The foundations were laid in 1734 and it was completed by Coke’s widow in 1764.

We use third-party platforms (including Soundcloud, Spotify and YouTube) to share some content on this website. These set third-party cookies, for which we need your consent. If you are happy with this, please change your cookie consent for Targeting cookies.Show Purposes

The Gothic

While Anglo-Palladian became the dominant national style, Britain’s Gothic architectural tradition retained its own appeal. Where Anglo-Palladian spoke of order and civic virtue, critics associated the Gothic style with the constitution and liberty, and with ancient British freedoms.

William Kent’s contribution to the Gothic style in Britain was to take it out of churches and colleges and into domestic settings. He undertook building projects at Esher Place, Surrey and Rousham House, Oxfordshire.

Landscape design

Kent’s landscape designs confirm his status as the artistic genius of the era, a father of the English landscape garden. In contrast with the French and Dutch fashions for formal gardens, Kent took his inspiration from the ideal landscapes of pastoral literature and painting. His design drawings are not detailed plans, but poetic evocations of the landscape effects he was attempting to achieve.

Kent’s gardens could be places of activity or places of reflection and solitude. Carefully crafted vistas lead the eye out beyond the garden into the surrounding countryside. He designed over 50 garden buildings which were positioned to act as picturesque focal points for views and also as places from which to contemplate the garden. His buildings vary from sober copies of ancient buildings to wild flights of fancy, from pyramids, triumphal arches and Chinese kiosks to grottoes and artificial ruins.

Kent was a painter, an architect, and the father of modern gardening. In the first character he was below mediocrity; in the second, he was a restorer of the science; in the last, an original, and the inventor of an art that realizes painting and improves nature. Mahomet imagined an elysium, Kent created many.

Horace Walpole

This content was created as part the V&A exhibition William Kent: Designing Georgian Britain, 22 March – 13 July 2014.

To learn more, visit: William Kent: designing Georgian Britain · V&A (vam.ac.uk)

https://www.hrp.org.uk/kensington-palace/history-and-stories/william-kent/#gs.apej5q

William Kent´s collection, visit: Search Results | V&A Explore the Collections (vam.ac.uk)